The 'Key Worker' Model of Service Delivery

Keeping Current. © Alison Drennan, MSc OT, Teena Wagner, MSc OT, and Peter Rosenbaum, MD, FRCP(C)

What is the 'Key Worker' Model?

The 'key worker' model is a method of service delivery involving a person who works in a guide role with families. This person acts as a single point of contact for a family, helping the family to coordinate their care, not only within the healthcare system, but also across systems (education, social services, financial resources, recreation, transportation, etc). The main concept of the key worker's role is to empower parents by providing them with support, resources and information tailored to meet their individual needs.

This activity is accomplished by a variety of means which may include:

- being available on a regular basis, and also when required by the family;

- helping parents understand the system(s) and, if required, helping them navigate the system(s);

- being present at various meetings/appointments if requested by parents;

- assisting with the interpretation of assessment results, or outcomes of meetings; and

- supporting the family's skills, and providing parents with additional skills or tools to facilitate empowerment.

Service delivery models which utilize a formal 'key worker' in the role described above are uncommon in the Canadian context. Many times 'care coordination' is taken on informally by professionals or nonprofessionals at various organizations, mainly children's rehabilitation centres. The 'key worker' model is most prevalent in the United Kingdom , as a result of the statutory guidance of the 1989 Children's Act.

There is a multitude of synonyms for 'key worker'; these include, amongst others, 'care coordinator', 'link worker', 'guide', 'guide worker', 'service coordinator', 'family support worker 'and 'family liaison worker'.

'Key working' is most often implemented for families of children with special needs. This model has also been implemented for people with mental health difficulties, older adult populations, and in palliative care. Drawing on the available literature, this report focuses on the key worker model for families of children with special needs.

Why is Key Working Needed?

An issue repeatedly highlighted in the literature is the need for effective care coordination for families of children with special care needs. It has been shown that the more health or development problems a child has, the more services they receive; this in turn is correlated with the number of sources of service, which in turn is related to a greater diversity of locations from which those services are provided. Not surprisingly, parents report that in this circumstance services are less family-centred. 1 Studies also show high levels of unmet needs for information, help with child's development, respite, aids, equipment, and financial help 2 . Parents report a constant battle to access information and services, and these battles increase parents' stress, which in turn impacts on their child's development. 2 Numerous research studies have also reported that parents want a single point of contact with services and an effective, trusted person to support them to get what they need. 2

Case Management vs. Key Working - What is the Difference?

Parents whose children need specialized services believe that they are best able to make decisions regarding services they receive. 3 Traditional case management is a process that matches the client's health care needs with the available services and resources. Case management, in most cases, does not involve coordination across all systems, individualizing approaches for different families based on their specific needs, or taking steps towards empowering parents

Who Takes on the Role of Key Worker?

The professions most frequently described in the literature that are employed in 'key worker' positions are social workers and nurses from a variety of practice areas. Occupational therapists, physiotherapists, psychologists and teachers are the next most frequently mentioned professionals who take on this role. Also often mentioned are workers with volunteer agencies, with the rationale for their effectiveness in this role being their highly specialized knowledge and capabilities for networking

Does the Key Worker Have the Potential to Provide Family-Centred Care?

Family-centred service is a philosophy and method of service delivery for children and parents which emphasizes a partnership between parents and service providers, focuses on the family's role in decision-making about their child, and recognizes parents as the experts on their child's status and needs. 4 Family - centred service specifies the process of service delivery to meet the needs of children and families. The key worker model specifies one possibility of how this might be accomplished, as it specifies the services and the delivery mechanism for those services.

The concepts inherent in the Measure of Processes of Care (MPOC) 5 are used here to illustrate the key worker model as a method of service delivery that has the potential to provide a family-centred service. The MPOC was designed to measures parents' perceptions of family-centred service, and is based upon specific behaviours that constitute the important aspects of care-giving as reported by parents. 5 These components of care are organized into five categories: Enabling & Partnership; Providing General Information; Providing Specific Information about the Child; Coordinated & Comprehensive Care for the Child & Family; and Respectful & Supportive Care.

Tables 1 and 2 use the MPOC categories to discuss the Roles and Responsibilities and Benefits of the key worker model of service delivery, respectively.

What are the Limitations of Key Working?

The literature speaks of the following shortcomings associated with the key working:

Although parents with a key worker are more likely to report a positive relationship with professionals than those without such a relationship, the availability of a key worker may not minimize the number of problems they experience with services. Such problems are often related to inter-agency collaboration and availability of services. 17

Some key workers feel dissatisfied and frustrated with their prescribed role, as they are not able to provide direct care utilizing their skills and expertise. 22

The effectiveness of this model is not well documented. The evidence is generally of a low level in terms of the research methods by which it has been gathered. The evidence is frequently in the form of satisfaction surveys and information gathered from qualitative studies including focus groups.

The simplicity of the idea of key working stands in stark contrast to the complexity of implementation. 8

Table 1: Roles and Responsibilities of the 'Key Worker'

MPOC Scale 1:

Enabling & Partnership

The key worker provides the family with the tools, resources, support, and guidance to carry out complex tasks and, when necessary within a partnership, assumes those tasks the family cannot handle. 6

MPOC Scale 2:

Providing General Information

An important function of the key worker is to provide families with general information. The key worker provides information in a flexible manner, tailoring the format, timing and content of information to the individual family's requirements.

MPOC Scale 3:

Providing Specific Information About the Child

The key worker provides specific information about the child, which includes answering questions about child's health needs and special needs. 7

MPOC Scale 4:

Coordinated & Comprehensive Care

The key worker provides coordinated and comprehensive care by ensuring access to, coordination of and delivery of services from different agencies. 6,8 In essence, the role of the key worker is to pull together all of the elements of each child's life. 9

MPOC Scale 5:

Respectful & Supportive Care

A key worker provides respectful and supportive care by providing emotional support ,2,10 and encouragement, 9 counseling parents and child, 10 linking families with other families for support, 11 and by supporting the families' skills & abilities to coordinate & provide the child's care. 9

Advocacy

(this is not a MPOC category, but is an additional role/responsibility of the key worker)

Key workers advocate for families and children with special needs. 12, 13 They also advocate at the community level to increase awareness and availability of services. 12

Table 2: The Benefits of Key Working as Found in the Literature

MPOC Scale 1:

Enabling & Partnership

- increased parental engagement and empowerment 14 and improved relationships between family, services and professionals 11,13

MPOC Scales 2 and 3:

Providing General Information and Specific Information about the Child

- greater levels of satisfaction with respect to information provision as reported by families with key workers 14

MPOC Scales 4:

Coordinated & Comprehensive Care

- r esulted in minimal problems with service coordination 16 and higher levels of satisfaction with care coordination reported by families with a key worker; 15

- increased navigability of the system by family and professionals; 13,17

- provided better and quicker access to benefits, services and practical help; 18

- decreased costs associated with unnecessary professionals' visits 19,20

MPOC Scale 5:

Respectful & Supportive Care

- increased ability to develop an open, trusting, supportive relationship between families and key workers; 21

- improved relationships between families, services, and professionals; 13

- decreased burden of care; 18

- improved family relationships, health, and morale 18

What General Implementation Principles Should be Considered?

General principles need to guide the implementation process of a key worker model of service delivery. Within the parameters of these principles, specific details may vary. Based on the literature, consideration of the following issues will facilitate the implementation of a service delivery model involving key working.

Service-Specific Principles:

The key worker service should :

- be family-centred rather than child-centred;

- be needs-led rather than service-led;

- entail a flexible, individualized approach;

- be a formalized program so it is recognized by professionals/practitioners across all agencies;

- be evaluated, monitored, and able to adjust to meet needs;

- include an overall Service Coordinator (i.e., to coordinate key worker services);

- be supported by a multi-agency steering committee; and

- have buy-in and ownership from management for longevity and maintenance of the program.

Role-Specific Principles:

- To support and empower key workers appropriately, the role should include:

- clearly defined job descriptions outlining roles, responsibilities, and limitations;

- protected time for the service, regardless of whether it is full-time or otherwise; and

- adequate support and training.

Key workers should :

- be accountable to the family, not perceived as working for an agency; and

- be a single contact, able to work across agencies.

Summary

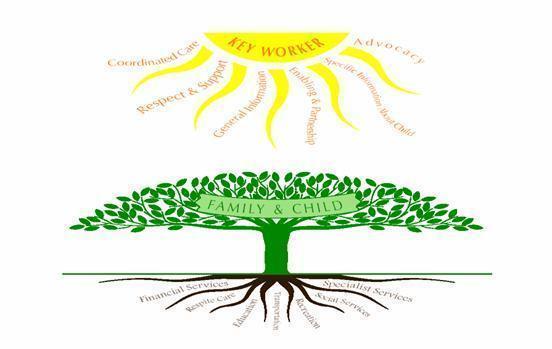

The following diagram summarizes the general ideas behind the key worker model. It illustrates the ability of the model to provide family-centred care, and as well the potential benefits of providing that care.

The key worker (the sun) empowers the family and child through family-centred care. This allows the family and child to grow and to be able to access the services and resources they require to support themselves. The various services are metaphorically illustrated as the roots of the tree. Just as the roots access the soil to allow the tree to grow and support itself, the key worker enhances a family's ability to access services.

Want to know more? Contact:

Peter Rosenbaum, Co-Director

Tel: 905-525-9140 x 27834 Fax: 905-522-6095